STANWOOD — A treatment center that would add up to 32 beds for those struggling with mental illness has drawn resistance.

Kandyce Hansen lives less than a half mile from the Arabian horse farm where the center has been proposed since early this year. She’s one of about a dozen neighbors who formed the North Stanwood Concerned Citizens, which opposes the project’s location. They argue an in-patient treatment center doesn’t belong in a rural neighborhood.

“This is a small community, we have very limited resources,” Hansen said in an interview.

Yet proponents say beds are sorely needed for psychiatric patients.

A rural setting is “an ideal setting for healing,” said Julie Melville, a Camano Island resident.

Melville is a member and immediate past president of the National Alliance on Mental Illness Skagit, which serves families in Stanwood, as well as Skagit and Island counties.

Melville supports the proposal. Twenty years ago, Melville would have been opposed to such a project because of perceived threats to her neighborhood, she said in an interview. Her views changed after several family members were diagnosed with mental illness and she mentored people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

“They are our neighbors; people may be surprised to hear that,” she said. “They come from all walks of life, folks you would never imagine having a mental illness.”

The in-patient facility would admit adults for involuntary treatment for stays of 90 or 180 days. In Snohomish County, there are just six psychiatric beds set aside for long-term stays.

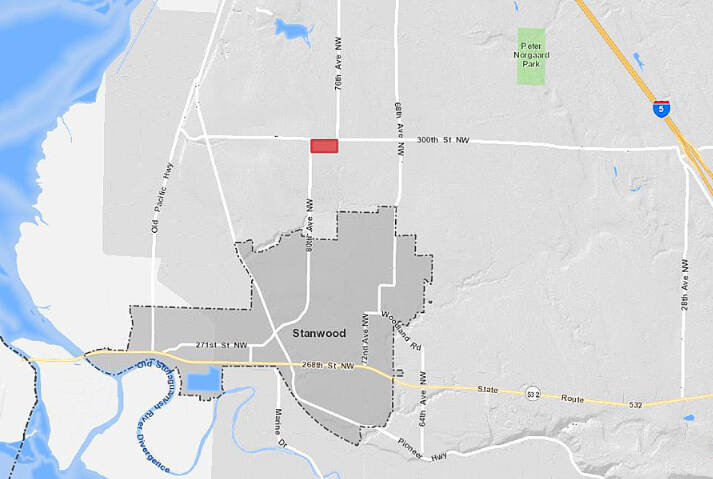

The center would consist of two 16-bed buildings at the southeast corner of 300th Street NW and 80th Avenue NW, north of Stanwood city limits.

Cows graze in nearby fields among single-family homes. Neighbors first learned of the proposal in early February, when postcards were mailed about development plans. An orange sign was posted on 300th.

Since then, dozens have submitted written comments and spoken at three town halls. Many raised concerns about security, traffic and why the site was selected near Stanwood.

Meanwhile, mental health advocates and others have spoken in support. Several told The Daily Herald their relatives with mental illness have faced delays finding a bed or were sent to other counties, even across the state. A new local facility could help, they said.

The facility would treat patients who have been civilly committed, not those in the criminal justice system awaiting mental competency evaluations, the Washington State Health Care Authority has said.

The project was headed to a permit hearing on Oct. 27, but the hearing was postponed due to a State Environmental Policy Act appeal. A neighbor filed the appeal on Oct. 3, alleging the county’s environmental review was “deficient” due to an issue over a boundary line adjustment. A new notice will be sent to all parties of record when a new hearing date is set, county spokesperson Jacob Lambert said.

The Stanwood-area facility has its roots in a sales-tax sharing deal between the Tulalip Tribes and the state.

In 2020, the two sides ended a years-long legal fight when the tribes agreed to spend $35 million to design and build a civil commitment center in Snohomish County outside the Tulalip Reservation. In exchange, the tribes would get a cut of the millions in sales tax revenue generated annually at the Quil Ceda Village shopping center.

The tribes applied for a conditional-use permit in late January, proposing to build the center on land it bought in 2011. It will build the first 16-bed facility and turn the keys over to the Health Care Authority, which will hire a behavioral health provider to run it.

In the future, the state may build the second 16-bed facility, if the Legislature approves funding. If the permit goes through, the first building could go up as soon as 2024.

‘Quiet of the country’

Drivers speed on 300th Avenue NW, a 50 mph road with no shoulders, Hansen said.

“I have seen many accidents occur, T-bones, cars in ditches,” she said, explaining she worries about patient safety.

However, it’s highly unlikely patients would be wandering the streets. The facility will be locked and outdoor areas secured by 12-foot, anti-climb fences. Staff will be trained in de-escalation techniques.

North Stanwood Concerned Citizens members argue an urban area would be a better site: closer to emergency medical services, transportation and out-patient facilities.

Neighbors have brought up concerns about personal safety. Patient escapes are rare. The Health Care Authority has stressed how those with mental illness are much more likely to be victims of crimes than perpetrators.

At a town hall meeting Aug. 22 in Stanwood, attendees asked about about patients being “discharged to the streets,” according to meeting audio obtained by The Herald.

“Discharge planning starts the day they are admitted,” Keri Waterland, director of the division of behavioral health and recovery with the HCA, told the audience. Staff offer help with housing and transportation, for example.

Patients will likely connect with out-patient services in the places where they lived, not necessarily in Stanwood, said Kara Panek, the state agency’s section manager for adult services and involuntary treatment, in an interview.

The Health Care Authority has advertised the center as created for Snohomish County residents. In reality, it will likely serve patients around north Puget Sound, Panek said.

A member of the public commented on the discharge process at the town hall in August. The man said he works at two in-patient psychiatric facilities in Skagit County.

“I’ve never ever seen anyone discharged out the door,” he said. “They are picked up by taxis, picked up by family members, they are taken to the bus station.”

Other neighbors say the facility will disrupt the peace.

“We like the quiet of the country,” Susann Hendrickson, a Lake Ketchum resident, told The Herald.

Hendrickson, who lives about 2 miles north of the site, worries about increased traffic on 300th. The facility’s entrance will be across from 76th Avenue NW, the only entrance to the Lake Ketchum neighborhood, a subdivision of about 430 homes.

The project is expected to generate 284 new daily vehicle trips, according to a traffic study. Due to limited sight distance, departing traffic will be limited to right-turns only on 300th. An 8-foot-wide shoulder will be added.

The site is zoned Rural 5-Acre (R-5), intended to “maintain rural character in areas that lack urban services,” county code states.

“They keep saying it will fit in with the surrounding area,” Hendrickson said, “but you cannot tell me that (two) 15,000-square-foot buildings will fit in with residential areas, horses and barns.”

‘A done deal’

Melville, of NAMI Skagit, wouldn’t be concerned about a 32-bed facility going up in her neighborhood.

If she lived near the center, she said she would bring over an extra worm bin to get compost going, explaining she’s a “worm farmer” who is passionate about organic gardening. The Health Care Authority lists gardening as one recovery activity in its “toolkit” on long-term treatment. There will be an outdoor patient patio and fenced yard for activities, the plans state.

“I wouldn’t want a Western State Hospital in my backyard, but that’s not at all what it is,” Melville said.

The 806-bed state-run hospital south of Tacoma has been plagued by problems for years and lost federal funding in 2018. The same year, Gov. Jay Inslee announced a five-year plan to shift mental health care from large hospitals like Western State to smaller, community facilities. The idea is to help patients maintain connections with family and friends.

The 32 beds near Stanwood are just a small piece of the puzzle. Other centers are going up around the state: 48 beds near Vancouver, 16 beds south of Olympia and 16 more beds in Everett.

Only a handful of people spoke in favor of the project at the town hall in August. Stanwood resident Beth Bryant read a supportive statement from Stanwood United Methodist Church Rev. Justin White.

“Imagine if one of your loved ones had a mental health episode and needed care, and you did not know what to do. This care facility could be a life saver for them,” White’s statement said.

In an interview, Bryant said she also supports the facility. As a former teacher, she said, she sees the need for mental health care. She added she understands how those who live “right across the fence” have concerns.

There are several in-patient treatment centers in rural areas. The Health Care Authority gave three examples: Telecare North Sound E&T near Sedro-Woolley; Cascade Evaluation & Treatment Center outside Centralia; and Recovery Innovations International opening outside Olympia.

The Health Care Authority played no role in site selection, Waterland told The Herald.

Keith Banes, with the Wenaha Group, represented the Tulalip Tribes at town hall meetings this year. He said the site north of Stanwood was a “piece of property … available to the tribes to meet the terms of the (tax-sharing) compact.”

Banes said the tribes considered alternative sites in Arlington and Monroe. Ultimately, he said, the North Stanwood site was selected because a mental health facility could be sited in the R-5 zone.

Members of the public expressed frustration the project seemed a “done deal” when it was announced in February.

Waterland said the Health Care Authority did not begin public outreach until after the permit application due to “timing.” According to emails obtained through a public records request, the Health Care Authority and the Department of Social and Health Services discussed the project as early as January 2021. Initially, there was confusion over which agency would take the lead, emails show.

An online town hall was held in March 2022, followed by in-person events on June 22 and Aug. 22, at the request of community members, Waterland said.

“We really do appreciate the feedback,” she said, adding she understands why some are nervous.

Snohomish County Council member Nate Nehring has shared similar concerns as neighbors.

“Public process ought to be more than just window dressing, so I am disappointed in the State’s handling of that to date,” he wrote in September in the email to a constituent, forwarded to The Herald. “I have no issue with the Tribes here, as they have been very transparent and have met with me on this subject.”

Nehring told The Herald he heard from many community members that questions went unanswered.

He wrote he supports a behavioral health facility in his district, but it would be “more appropriate in an industrial area such as Smokey Point,” closer to services.

Nehring sent a letter, along with Stanwood Mayor Sid Roberts and State Rep. Greg Gilday, R-Camano Island, in February to oppose the application.

In a public comment in September, the Stanwood mayor said he feels “rather neutral” now after meeting with the Health Care Authority and representatives of the tribes, according to comments reviewed by The Herald. The city has not taken an official position on the project, which is in unincorporated Snohomish County. The project will be served by city water.

In the comment, Roberts noted he doesn’t share the safety concerns of others.

“I view the potential residents who would live in this facility as people who are ill just like any other person who is ill,” he wrote. “Their illness just happens to be mental illness.”

‘A drop in the bucket’

The Stanwood project would raise the total of long-term beds in the county to as many as 38. Currently, there are just six, part of Providence Regional Medical Center’s psychiatric ward in Everett, opened in 2021.

And statewide, there are just 164 beds for 90- or 180-day stays, according to a map from the Health Care Authority. The state agency plans to add another 224 beds statewide in the near future.

Other facilities in Snohomish County focus on shorter treatment, such as Compass Health’s 16-bed facility in Mukilteo or the 115-bed Smokey Point Behavioral Hospital in Marysville.

Under state law, patients can be involuntarily hospitalized for up to five days if a designated crisis responder determines the person is a danger to themselves or others or cannot care for their basic needs.

If needed, a psychiatric provider can file a petition for 14 more days of involuntary treatment. A court can order the additional treatment if they find the person meets the legal criteria. After that, the court can order longer involuntary treatments — like the 90- or 180-day stays planned north of Stanwood.

A problem, Panek said, is that long-term patients sometimes occupy beds meant for short-term patients.

“It kind of messes up our system, we don’t have people moving through as they should,” she said.

Patients are sometimes held in emergency rooms if no beds are available, a practice called “psychiatric boarding.”

Karen Schilde, an Everett resident and board member of NAMI Snohomish County, said her relative has had 15 involuntary hospitalizations. “Almost every time,” she said, the relative has waited in the emergency room for a bed to open, for as long as two days.

“They have often looked from all the borders from one to another” for a bed, said Schilde, who supports the Stanwood facility.

Lauren Simonds, CEO of NAMI Washington State, spoke about the statewide shortage of beds at the town hall in Stanwood in June. She cited data from the Washington State Hospital Association in 2021 that shows 7,607 declines or “deferrals” for psychiatric patients needing a bed. In more than half the cases, patients were declined because no bed was available.

With beds in short supply, patients can end up several counties away from their families.

A Snohomish County resident recalled a close family member who has had six involuntary stays outside the county. The farthest was in Spokane. The woman asked for anonymity to minimize harm to their family due to shame around mental illness.

“They don’t really have a family base to depend on,” she said. “It’s really important to be able to keep the connection during the traumatic times so it doesn’t get broken.”

The woman called the proposed 32 beds near Stanwood a “drop in the bucket.”

“It doesn’t come close to serving the need,” she said. “These facilities should be like libraries — every community should have them.”

Are you or someone you know in crisis?

Call or text 988 for a 24-hour crisis hotline or dial 800-584-3578.

Jacqueline Allison: 425-339-3434; [email protected]; Twitter: @jacq_allison.

Gallery

More Stories

Thoughts as of late: on evolving, growing & that tiny voice inside

County Health Officials Report 17% Increase in Tuberculosis Cases

10 Most Nutrient-Rich Foods To Include In Your Diet